Soft drink companies to stop high school soda sales

Thursday, May 4, 2006

Most U.S. soft drink companies will stop selling their soda products at high schools across the nation as part of a soft drink industry deal that aims to reduce childhood obesity.

The agreement, announced Wednesday morning by the William J. Clinton Foundation, means that the nation's biggest beverage distributors, Coca Cola Co., Pepsico, Cadbury Schweppes PLC, and the American Beverage Association, will pull their soda products from vending machines and cafeterias in schools serving about 35 million students, according to the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, a joint initiative between the Clinton Foundation and the American Heart Association.

"This is an important announcement and a bold step forward in the struggle to help America's kids live healthier lives," said Bill Clinton, according to a press release from the foundation. "These industry leaders recognize that childhood obesity is a problem and have stepped up to help solve it. I commend them for being here today and for taking this important step. There is a lot of work to be done to turn this problem around but this is a big step in the right direction and it will help improve the diet of millions of students across the country."

Under the agreement, high schools will still be able to purchase drinks such as diet and unsweetened teas, diet sodas, sports drinks, flavored water, seltzer, and low-calorie sports drinks for resale to students.

The companies plan to stop soda sales at 75 percent of the nation's public schools by the 2008-2009 school year, and at all schools in the following school year. The speed of the changes will depend in part on school districts' willingness to change their contracts with the beverage distributors, the release said.

California had already banned soda sales at Logan and other state high schools, starting in July 2007, under a bill signed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. "California is facing an obesity epidemic," he said at the time. He said he plans for the ban to be the first step in creating a healthier California.

The bill banning soda sales, SB965, was introduced last September by Senator Martha Escutia of State Senate District 30 in Southern California. SB965 is one of several bills signed into law to "eliminate junk food and soda from campuses, and to increase the amount of fresh fruits and vegetables available to students," said Schwarzenegger. The new law will go into full effect by July 1, 2007.

State law already bans soda sales at the lower grade levels.

Elsie Lee Szeto, the director of Food and Nutrition Services of New Haven Unified School District in Union City, California, said that, under the new law, no less than 50 percent of all beverages sold to students between a half hour before school begins and a half-hour after school will have to meet specific criteria that include alternatives like fruit based drinks that are comprised of no less than 50 percent fruit juice and have no added sweeteners. All milk sold will be two percent fat milk, soy milk, and other similar non-dairy milk.

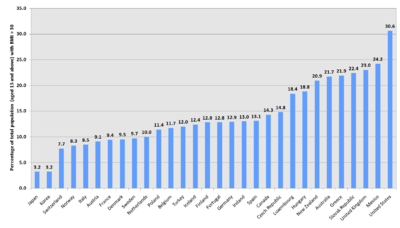

About 16 percent of our nation's children and adolescents are overweight or obese – nearly four times more than forty years ago, according to the Alliance for a Healthier Generation.

According to the Center of Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), a non-profit advocacy group in Washington D.C., two out of three teenagers in California drink soda everyday. The average intake for males 13 to 18 is three or more cans of soda a day.

A recent study by researchers of Children's Hospital Boston showed a connection between consumption of sugary drinks and childhood obesity.

Children's Hospital Boston's Cara Ebbeling, PhD, and David Ludwig, MD, PhD, led a controlled trial for 103 children ages 13 to 18. Half of the teens, picked randomly, were sent non-caloric beverages of their choosing. The remaining teens were asked to continue their regular eating and drinking habits as a control group.

After six months, the group that had received the calorie-free drink deliveries had an 82 percent decrease in the consumption of sugary drinks, while the control group continued unaffected. The body mass index of the drink delivery group decreased, while the control group had a slight increase. Other factors such as exercising and television viewing did not change in either group.

Ebbeling concluded that one 12-oz sugary drink every day converted to a one pound weight gain over 3 to 4 weeks. "It should be relatively simple to translate this intervention into a pragmatic public health approach. For example, schools could make non-caloric beverages available to students by purchasing large quantities at low costs," she said.

The agreement announced today "is really the beginning of a major effort to modify childhood obesity at the level of the school systems," said Robert H. Eckel, president of the American Heart Association.

Sources

edit- Patrick Hannigan. "Coke, Others, to Stop Soda Sales at Logan, Nationwide" — James Logan Courier, May 3, 2006

| This page has been automatically archived by a robot, and is no longer publicly editable.

Got a correction? Add the template {{editprotected}} to the talk page along with your corrections, and it will be brought to the attention of the administrators. Please note that the listed sources may no longer be available online. |