NASA detects dry, dusty atmospheres on extrasolar planets

Friday, February 23, 2007

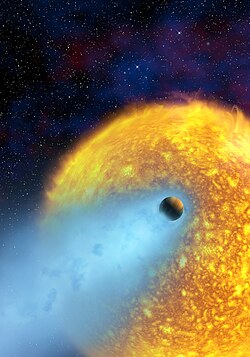

Photo credit: European Space Agency, Alfred Vidal-Madjar (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS, France) and NASA.

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope made news this week when it was announced that the space observatory had, for the first time, captured enough light to detect molecules in the atmospheres of planets outside the solar system.

The planets are too far away to be observed directly with current technology, but by measuring the spectra of each planet when visible with its star, and again when the planet was hidden behind its star, the teams were able to determine the measurements of the planets spectra.

In a paper published in the February 22 issue of Nature, Dr. Jeremy Richardson of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center presented measurements of HD 209458 b, a hot, Jupiter-like planet located 153 light-years from Earth, in the constellation Pegasus. Richardson's team found a peak in the infrared spectra and was able to determine that the atmosphere of HD 209458 b likely consisted of clouds of silicate dust. Dr. Mark Swain of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory led another study of HD 209458 b, and found similar results.

Another team, led by Dr. Carl Grillmair of Spitzer Science Center at Caltech, performed a similar study of HD 189733b, 63 light-years away, in the constellation Vulpecula. Dr. Grillmair discusses the results: “It was believed to be fairly straightforward that these planets would have a lot of water in them, for one thing, very hot water. These planets, these hot Jupiters very, very close in to their parent stars are 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit or so, so it's not a pleasant place to live. And what we found instead and what the other group found for this completely different planet around another star, is that the spectrum is essentially flat. It really doesn’t show any of the features we would have expected from water.”

"The theorists' heads were spinning when they saw the data," adds Dr. Richardson. "It is virtually impossible for water, in the form of vapor, to be absent from the planet, so it must be hidden, probably by the dusty cloud layer we detected in our spectrum."

Dr. Grillmair: "The observations are showing us that things are not the way we expected them. And so there'll be a big push to get a lot more data while Spitzer is still alive. I think this will ultimately be one of the most important legacies of the Spitzer Space Telescope, unanticipated as it was before launch. I think it will become extremely important in the future." The telescope was launched in August of 2003 with a maximum expected life cycle of 5 years.

"With these new observations, we are refining the tools that we will one day need to find life elsewhere if it exists," said Swain. "It's sort of like a dress rehearsal."

Dr. Swain's and Dr. Grillmair's studies are pending publication in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Sources

- L. Jeremy Richardson, Drake Deming, Karen Horning, Sara Seager and Joseph Harrington. A spectrum of an extrasolar planet. Nature, 2007; 445: 892-895. arVix

- C. J. Grillmair, D. Charbonneau, A. Burrows, L. Armus, J. Stauffer, V. Meadows, J. van Cleve, D. Levine. "A Spitzer Spectrum of the Exoplanet HD 189733b" — arXiv, February 19, 2007

- M.R. Swain, J. Bouwman, R. Akeson, S. Lawler, C. Beichman. "The mid-infrared spectrum of the transiting exoplanet HD 209458b" — arXiv, February 21, 2007

- "NASA's Spitzer First to Crack Open Light of Far Away Worlds" — NASA, February 21, 2007

- "Hot, Dry and Cloudy" — NASA, February 21, 2007

- "Hunting for Molecules on Faraway Planets" — JPL, February 21, 2007

| This page has been automatically archived by a robot, and is no longer publicly editable.

Got a correction? Add the template {{editprotected}} to the talk page along with your corrections, and it will be brought to the attention of the administrators. Please note that the listed sources may no longer be available online. |